A Young Person's Guide to an AI-Driven Future (Part 1)

Prof. Jocelyn Maclure of McGill University discusses AI's implications for the young generation.

Jocelyn Maclure is a full time professor of philosophy at McGill University, currently holding the position of Stephen A. Jarislowsky Chair in Human Nature and Technology. First known for his work in ethics and political philosophy, his book Secularism and Freedom of Conscience, co-authored with Charles Taylor, was published in 10 languages.

Now, he has turned his focus towards the philosophical questions and ethical dilemmas introduced by the progression of artificial intelligence and its impact on the public sphere. In this two-part series, we attempt to bridge the gap between theoretical concerns surrounding AI and its real-world implications.

Question 1

Artificial Intelligence seems to be the discussion of every other news article, opinion piece, and social media post. However, it is often difficult to identify trustworthy sources, especially when industry leaders are incentivised to drive investment hype. For example, some tech CEOs predict that AGI (a hypothetical AI with human-level general intelligence) will be reached within a few years, while more sceptical researchers label it impossible.

You have previously written against AI inflationism. What is your assessment of the current state of the AI industry, and how can students navigate the various ‘insights’ into the future of AI as they seek to take advantage of this changing landscape?

Prof. Maclure: “Yes, you are right. Public discourse on the future of AI is even harder to navigate than you suggest because the self-interested hype fuelled by industry leaders is supported by the genuine concerns of independent researchers in various academic disciplines, including deep learning pioneers in Canada such as Yoshua Bengio and Geoff Hinton. This lends plausibility to the strategic and over the top claims and predictions of industry leaders.

The view that we may be on the verge of reaching AGI, artificial superintelligence or strong AI is difficult to ascertain because “intelligence” refers the different cognitive capacities, and it remains unclear how modalities such as, for instance, our sensory perceptions, our emotional responses to the world, our practical knowhows and our capacity for logical reasoning and abstract thought interact and contribute to the general intelligence of human and nonhuman animals. Moreover, we still don’t understand how and why some embodied living organisms are conscious, i.e. endowed with the machinery that make subjective experience, i.e. the capacity to feel, possible. Such uncertainty makes speculative thought unavoidable.

Edmund Husserl thought that the central slogan of the philosophical movement known as phenomenology was “back to the things themselves”. To go back to your question: I recommend a form of realism: let’s direct our attention to the actual capacities and limitations of the most advanced AI systems, and compare them with what we call intelligence allows humans and other animals to do. I defend a deflationary view about AGI because I see general intelligence as the outcome of a long biological and cultural evolution.

Deep learning techniques may one day give us self-driving vehicles that are safe most of the time and large language models that give plausible answers to our queries, but this is a far cry from the cognitive powers of humans who strive to survive and flourish. I understand that CEOs have an interest in fuelling the hype. I have a harder time understanding why serious scholars trained in computer science don’t engage more deeply with biology, psychology and philosophy if human intelligence is the model and benchmark for machine intelligence.

It should at the very least be acknowledged that the hypothesis that what we call general intelligence can be instantiated by a radically different (nonbiological) physical substrate is radical and highly speculative.”

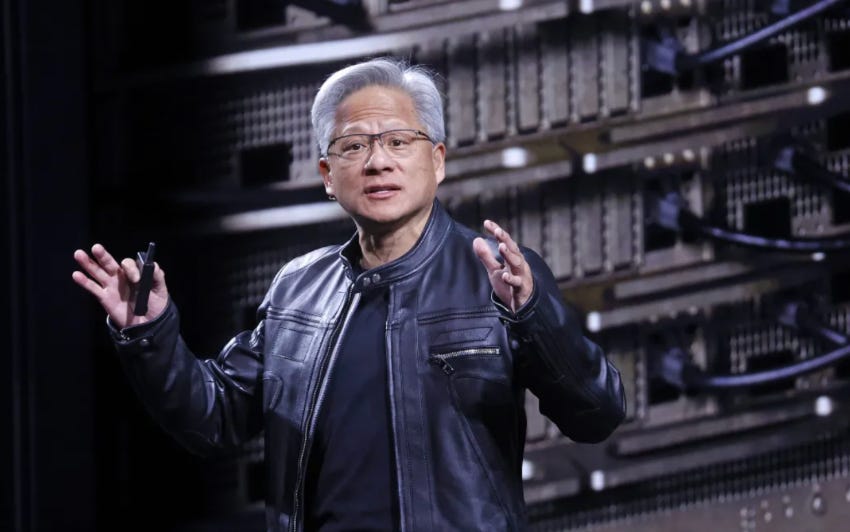

“There’s a belief that the world’s GDP is somehow limited to $100 Trillion. AI is going to cause that $100 Trillion to become $500 Trillion” - Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia

Question 2

There’s no doubt that LLMs can be helpful assistants, but they are increasingly being used to make important decisions across all facets of life. While this might provide convenience and ease in the short term, outsourcing our thinking to tools we do not fully understand could be detrimental to both our intellectual development and sense of personal autonomy.

To what extent can Artificial Intelligence models be of genuine assistance to young people seeking guidance, and how should we evaluate our own practices surrounding the use of these tools?

Prof. Maclure: “It is uncontroversial that human beings use tools and techniques to extend their cognitive powers, and that these artefacts in turn transform human nature. When we offload some cognitive or physical work to a machine, we must be clear about both the benefits and the costs. It should be stressed that students in all disciplines must develop their intellectual capacities and learn the fundamentals if they wish to be in a position to make a wise and fruitful use of conversational AI systems.

My concern is that the easy access to powerful chatbots incentivize people to skirt the demanding process of developing their skills and learning the basics. In addition to all the essays that I had to write as a university students, I wrote dozens of articles for our student newspaper. This was demanding but incredibly formative. Thinking long and hard about how to introduce a topic or what you make of a particular theory, facing the blank page, writing a couple of paragraphs and deleting them…these are all, as far as I can tell, necessary means to become a good thinker and writer.

Similarly, Large Language Models may help programmers be more productive, but how will you spot a bug in AI-generated code or create original computer programs if you didn’t develop your skills independently?

One policy that I recommend to students is to make sure that AI chatbots do not become their only or even main access to knowledge and discourse. Sifting through the links proposed by a search engine, looking directly at the table of contents of a magazine or of an academic journal, reading an author in the text rather than relying on the summaries produced by a conversational system, discussing with a fellow student…all these forms of mediation remain irreplaceable.

One could reply that some are using generative AI in highly creative and productive ways. This is surely true, but this requires considerable work on the prompts and the preexisting capacity to assess the outputs of the AI. LLMs are designed to predict what usually follows a string of symbols, not to produce original thoughts. Personally, I prefer to spend time engaging with other philosophers, scholars and writers than to brainstorm with a statistical engine.”

To Be Continued…